Attempts to Understand Cardiac Arrest NDEs

So, now we come to the really important question: what happens when an NDE occurs during a cardiac arrest, and why is this important?

The first point is that signs of cardiac arrest are the same as clinical death. There is no detectable cardiac output, no respiratory effort, and brainstem reflexes are absent. If you are in this state and I put a tube down your throat, you will not cough. You will have dilated pupils. Your blood pressure has fallen to zero. You are, in fact, clinically dead. Even if I start cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), I cannot get your blood pressure any higher than 30 millimeters of mercury, and this is not going to produce an adequate blood flow to your brain.

A number of studies show that the longer CPR is continued, the more brain damage occurs. So it is not an ideal intervention. We know that after a cardiac arrest, both NDErs and nonNDErs suffer brain damage, but we do not know whether the amount of brain damage in the two groups is the same or different. During CPR, you are not going to be able to perfuse – that is, force an adequate amount of blood through – the brain. When the heart does finally start, the blood pressure rises, and there is a slow resumption of circulation and lots of technical reasons why your brain function does not return instantly. And the point to remember is that your mental state during recovery is confusional.

What should be clear to you now is that it is not a good thing to have a heart attack. In their 1999 studyof cardiac arrest and brain damage, Graham Nichol and his colleagues found that out of 1,748 cardiac arrests patients, only 126 survived (Nichol, Stiell, Hebert, Wells, Vandemheen, and Laupacis, 1999). Most units range between 2 and 20 percent resuscitation rates. Eighty-six of Nichol’s survivors were interviewed, and most of the people who were resuscitated had evidence of brain damage.

Simultaneous recording of heart rate and brain output show that within 11 seconds of the heart stopping, the brainwaves go flat. Now, if you read the literature on this, some skeptical people claim that in this state there is still brain activity, but, in fact, the data are against this in both animals and humans. The brain is not functioning, and you are not going to get your electrical activity back again until the heart restarts.

The flat electroencephalogram (EEG), indicating no brain activity during cardiac arrest, and the high incidence of brain damage afterwards both point to the conclusion that the unconsciousness in cardiac arrest is total. You cannot argue that there are ‘‘bits’’ of the brain that are functioning; there are not. There is a confusional onset and offset, and there is no brain-based memory functioning. Everything that constructs our world for us is, in fact, ‘‘down.’’ There is no possibility of the brain creating any images. Memory is not functioning during this time, so it should be impossible to have clearly structured and lucid experiences, and because of brain damage, memory should be significantly impaired, and you should not be able to remember any experiences which occurred during that time. Now, that raises interesting and difficult questions for us, because the NDErs say that their experiences occur during unconsciousness, and science maintains that this is not possible.

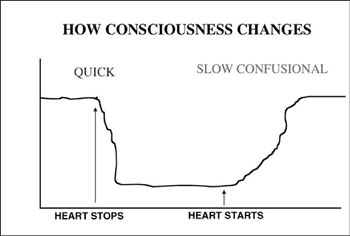

Figure 1

Changes in consciousness during cardiac arrest.

Figure 1 is an illustration I have drawn that I hope is helpful. The height of the line above the x axis shows the intensity of consciousness, and the squiggly line represents the level of consciousness. When the heart stops, the line starts to dip, and consciousness is lost. So you are going along conscious, your heart stops, and there is a very quick descent into unconsciousness. Those of you who have ever fainted will agree that when you faint you lose consciousness very quickly. So you lose consciousness, then you are unconscious, and then the heart restarts, so science says the NDE cannot occur while you are unconsciousness; that is the pink area in the diagram. Now, as you slowly regain consciousness, the slow recovery is all confusional, so the NDE cannot occur there.

So then, as far as science is concerned, the NDE cannot occur at the point the heart stops, it cannot occur at any point during the period of unconsciousness, and it is unlikely to occur at the point of confusional arousal, because it is not typical of that level of consciousness; and if it occurred after recovery, the NDErs would say it occurred after recovery, because they know they have recovered. So there are real difficulties in accepting that the NDE happens when the NDErs say it happens: during unconsciousness. So are you beginning to feel the significance of the timing of the NDE both for neuroscience as well as for our understanding of the NDE?

One of the major models we have of the NDE at the moment is the ketamine model. During cerebral anoxia, when the heart stops and there is no oxygen supply to the brain, there is widespread release of a chemical called glutamate, an NMDA agonist which leads to high nerve cell stimulation rates and chaotic firing in the brain. Ketamine is an anesthetic drug that acts like glutamate and is sometimes used as a street drug because of its pleasant subjective effects. Experimentally, ketamine leads to some NDE phenomena. Evgeny Krupitzky and Alexander Grinenko (1997) used ketamine in psychotherapy with alcoholics and found that it resulted in the same sorts of changes that people have with NDEs. Their patients became more social, more creative; more concerned with self-perfection and with achievement in life; more spiritually content; more interested in family, education, and social values; and more individually independent – many of the changes that NDErs have. Does that mean that the experiences are the same? Is it the NMDA stimulation that produces the NDE?

Well, look at this example of a ketamine experience, taken from Karl Jansen’s 2001 book, Ketamine:

... I found myself as a bodiless point of awareness and energy floating in the midst of a vast vaulted chamber. There was a sense of presence all around, as though I was surrounded by millions of others, although no one else could be seen. In the center of the chamber was a huge, pulsing, krishna-blue mass of seething energy that was shaped in a geometric, mandalic form ... . Then suddenly, I was back in my body, lying on my bed. ‘‘Wow,’’ I thought, ‘‘it’s over. How abrupt!’’ I tried to sit up. Suddenly, my body was gone again and the room dissolved into blackness of the void, my reality being quickly pulled out from underneath my feet, like a hyperspatial magician’s tablecloth trick. (p. 243)

NDErs, is that like your experience? No, it is not. There are some similar features, but there are other features that are very different.

So although the ketamine model is the best scientific candidate so far to account for the NDE in cardiac arrest, it cannot explain every feature of NDEs. And I am not sure that even if we say that the NDE is a ketamine-like experience, we can, in fact, completely understand the whole of the NDE during cardiac arrest. Because we are left with the problem of exactly when does the NDE occur? And the only way you can get an answer to this is through out-of-body experiences (OBEs).